Nobody will ever deprive the American people of the right to vote except the American people themselves and the only way they could do this is by not voting. – Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Visit Facebook any day of the week and you’ll see no shortage of political divisiveness, rants about corrupt government, and frustrations that American life as we know it continues to go from bad to worse. Is it any wonder that when people stay away from the ballot box on Election Day, it’s usually because there are either no candidates they feel they can trust or they’re convinced that their votes won’t make even an angstrom of difference?

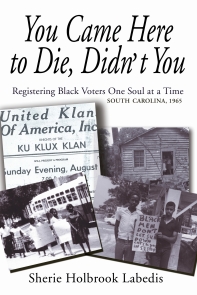

During the turbulent 1960s, a young white California coed seized an opportunity to step up for something she believed in and embarked on a bold mission to register black voters in the Deep South, a decision that put her face-to-face with staggering poverty, rampant illiteracy, and the Ku Klux Klan. In her moving memoir about the Civil Rights Movement – You Came Here to Die, Didn’t You? – author Sherie Labedis paints a compelling picture of an era that is only a scant 50 years in the rearview mirror but which still resonates today.

Interviewer: Christina Hamlett

**********

Q: A lot of the best writers often declare that they were voracious readers growing up. Was this the case with you?

A: I had two passions growing up. One was riding my horse and the other was reading. My students often don’t like to read, but it’s the best way to flights of fantasy and trips to foreign lands. In high school I took a class called Advanced Reading. We had to read books from a list colleges would expect us to know and we kept a journal of our responses. My favorite author was/is John Steinbeck. My father used to play in Zane Grey’s backyard and he wrote about the West, so he was a usual companion. I also enjoyed the breadth and detail in books by Tolstoy.

Q: What/who are you reading now?

A: My husband and I are reading The Thurber Carnival by James Thurber aloud to one another. I have just finished Ken Follett’s Winter of the World, book two in his Century Trilogy. South Carolina: A History by Walter Edgar helps me understand the “whys” of my book. I am just beginning Carol Ruth Silver’s Freedom Rider Diary: Smuggled Notes from Parchman Prison.

Q: Was the craft of writing something that came easily to you when you were a student at Ponderosa (coincidentally, our shared alma mater)?

A: I was a very successful English student. I loved the little creative writing I did. However, I couldn’t get the knack of writing essays and reports until I started teaching.

Q: What did you imagine yourself doing as a career after graduation and who or what was the strongest influence in shaping that dream?

A: I didn’t know “what I wanted to be.” Cowboy was high on my list and I had great math skills. I needed more information on what the possibilities were. You and I went to a small high school with limited offerings. I transferred to the University of California Berkeley. Their schedule of classes filled a book. I didn’t even know what many of the words meant. I’d found the place to discover what the possibilities were.

Q: Where did your passion for civil rights begin and what led you to volunteer?

A: I blame an English teacher and my book is dedicated to him. Television brought all the pain and suffering of the Civil Rights Movement into our living room. My English and social studies teachers considered it their responsibility to get us to pay attention. Bruce Harvey, the Advanced Reading English teacher asked the class what we were willing to die for. It was a rhetorical question for most of the students. Not for me. I wanted to know. When I arrived at UC Berkeley, I was quite aware that the answer to that question was part of the possibilities I would consider.

Two events moved me. One was in 1964 and, in the world of civil rights, it was called Freedom Summer. Black civil rights organizations recruited white college students to go to the Deep South to register black voters. Mississippi and Alabama had made it absolutely obvious that they would not allow integration and that they didn’t mind terrorizing and killing blacks to keep it from happening. Civil rights organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) thought that if white college students were beaten and killed on television, racists might back down. This was a miscalculation. Three voter registration workers, Mickey Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman, disappeared in Mississippi. Schwerner and Goodman were white and Chaney was black. It was forty-five days before their bodies were found, killed by the Ku Klux Klan. How could that happen in my country?

The second event was the Selma March in March of 1965. Six hundred blacks, men, women, children and old folks determined to march from Selma, Alabama, fifty-four miles to the statehouse steps in Montgomery to get down on their knees to pray for the right to vote. They never got out of Selma. They were stopped by a wall of police on horseback, carrying clubs, guns, and tear-gas. The beatings were so severe and so widespread the day is known as Bloody Sunday. Something in me snapped. I was now eighteen and when Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke at colleges asking for volunteers for a second Freedom Summer, I signed up with his Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Q: You were only eighteen, white middle-class and educated when you arrived in Pineville, South Carolina. You write that you were simultaneously horrified and overwhelmed. Why?

A: My parents were struggling to be middle class. Even so, I had a horse. We could come and go as we pleased. We had food, a warm home and, even though my mom made most of my clothes, we had all the clothes we needed. We had medical care. My dad had a car and, although it was an old clunker, my mom had one, too. When I was accepted to Berkeley my mom had to get a job at the post office to pay my way. We didn’t get what we wanted when we wanted it – sometimes we never got “it.”

The black world of South Carolina was the opposite of what I had known. In Charleston I learned that black people didn’t have health care when I met a woman dying with a rotting leg that could be smelled for blocks. Flies flew around a sore full of pus and her leg ballooned below it. I was sure “someone” in the black community would do something. I was told to report the problem to the church and they would do the best they could.

People were starving, barefoot, overworked and illiterate. They had mules and wagons, not cars. Most had no electricity or telephone in their tumbledown cabins, some of which had existed during slavery. Plumbing was outside including the pump for water. They were controlled by the white power structure and the Ku Klux Klan. We were there to help them register and vote because until they did, nothing would change.

Q: Knowing that three volunteers had been murdered during Freedom Summer in 1964, how did your family react to your wanting to leave a sheltered upbringing in Northern California and immerse yourself in the thick of poverty, racism, illiteracy and Ku Klux Klan violence?

A: Remember the adage, “You reap what you sow.” I’m afraid that is where they found themselves. They taught us to do what we thought was right. If we believed it, we had to commit to it. They had no idea where that philosophy would lead. They didn’t preach at my brother and me, they modeled the behavior for us. So, when I showed up and said I was going south, they were in a hard place. They were afraid. They were angry. They gulped and backed me up.

Q: Speaking of the KKK, what sort of tactics did they employ to try to encourage you and your fellow volunteers to leave?

A: The most frightening situations involved fire at the elementary school and the church where we had our mass meetings. They did drive-bys. They shot into our parking lot. One night several pickups pulled up and turned their lights on high and just sat there while we cringed inside the office. I was driven off the road and there were miscellaneous beatings and arrests.

Q: Looking back, what was the biggest obstacle you had to overcome as the veritable stranger in a strange land?

A: I was one of three white volunteers from the Bay Area. Our job was to get blacks to register to vote regardless of the consequences and one of those consequences might be death. Other possible consequences included losing one’s job, being taken off the food subsidy list and there was always the Klan. So here I was at eighteen going door by door trying to get these folks to believe me and trust that what I was telling them was the truth. “Trust and believe.” Now why would black Americans – they were called “colored” then – not trust white people? Two hundred and fifty years of history was part of it. A second reason was that most of them had never been “touching” close to white people before. Theirs was a world where they had to step off the sidewalk or cross the street if a white person walked toward them. Third, every rule of southern culture was supported by violence and retribution.

We were aliens. We came from 3000 miles away. We had different ideas, manners and language. Language was a major problem. The people of Pineville, where I spent most of the summer, had a Geechee or Gullah accent. The Gullah People, who came from the west coast of Africa, live on the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina and Georgia. Theirs is the most complete and oldest “African” language in the United States. I expected to hear a southern accent, not an African dialect and it was very difficult to understand. We, on the other hand, spoke collegeese – long sentences made up of big words about things that were largely unimportant to them. Stated simply, we wanted them to risk their lives on something that probably couldn’t happen and they didn’t trust us, didn’t like us, were afraid of us and couldn’t talk to us.

Q: What is something about the Civil Rights Movement that most people don’t know?

A: One thing is that it was made up of “common” people. Local black teenagers – high school students – did most of the work for our project. We didn’t have a Martin Luther King, Jr. Newspaper men weren’t hanging around to watch what happened. No photographers caught the flames when our church was burned to the ground. We were just folks who thought change was necessary and we were willing to work until that change happened.

Most of the people I knew were not nonviolent. I was in a farming community. Men carried rifles because they were hunters and because they wanted to protect their families. If we took kids to a demonstration, we frisked them first to be sure they “seemed” nonviolent.

Recently I met a black woman who was part of The Movement in Atlanta, Georgia, in the early sixties. She was interested in my book, because she didn’t know there were white people involved in The Movement. Freedom Summer recruitment was about 1000 whites. Our Second Freedom Summer recruitment was about 400. Whites were part of the Freedom Rides, but most of the demonstrations were carried out by blacks. However, whites did take part.

Q: Tell us about some of Pineville’s bright spots that reinforced your commitment to the causes you believed in.

A: Let me refer you to your “Share your favorite scene from the book” later in thisinterview.Mrs. Crawford made a conscious decision to trust me with her life. Each time someone got on the bus to go to the courthouse they trusted us. That’s incredibly heady for an eighteen-year-old considering what the dangers were. This is my best example of “connecting” with local folks. It just took months to get to this point.

Q: If you were newly graduated today, where would you go to make a difference?

A: Register and vote. Pay attention to the issues. If you want to “go” somewhere, there are still a Peace Corps and a Teacher Corps. Many churches have projects helping the poor and disadvantaged here and abroad

Q: What inspired you to write You Came Here to Die, Didn’t You?

A: I have a South Carolina family I will describe in another question. We’ve been family since 1965. In 2000 I took my husband Joe down to meet them. He made a video of the family reunion our visit engendered. Later that year I was going to have lunch with a dear friend. I wanted to give her a special gift, so I took the video and shared it with her. “You have to write a book about this,” she said. She edited every word. The book went its own way as books will and it is not about the Sarah Butler family, but it definitely started with them.

Q: What’s the story behind the title you gave your book?

A: Let me share an excerpt from my book.

Monday, June 14, 1965

“You came here to die, didn’t you.” It isn’t a question. It’s a challenge from a scrawny Negroteenager in faded bib overalls. His bare chest glistens in the hot Georgia sunshine. He reeks of body odor and my stomach lurches as I look up at his black eyes, then down to his unshod feet in the grass.

I’m standing on the sidewalk at Morris Brown, a Negro college in Atlanta. The Civil Rights Movement is front-page news across the United States. As an eighteen-year-old, white, female voter-registration volunteer from California, I’d expected to be applauded upon arrival for a week of voter-registration training. Instead of a welcoming committee and pep rally, only this young man’s almost angry dare welcomes me.

“I’m talkin’ to you,” he snaps. I force myself to meet his eyes. “If you didn’t come here to die, it’s time you git back into that car and head back to New York, Chicago or wherever you come from.”

Q: Share your favorite scene from the book.

A: Canvassing I met a lady named Rebecca Crawford. She lived alone in a little cabin. She told me she had registered, but she hadn’t. I tried to convince her to go to the courthouse with us – to help other folks register. She said she would, but I was sure she wouldn’t. When the bus pulled out of the parking lot going to the courthouse, she was walking up the road to catch it. Once on the bus she told me she had never registered and that she could neither read nor write. I told her all she had to do was write her name. She tried, but the bus ride was too short. I promised to “Come and learn me how to write so I cain regster next time.” My favorite scene is about that day.

The road is just as long and as hot as before. Far ahead, I can see someone moving toward me. I recognize the straw hat first, then a basket on her arm and finally that beaming, delighted face.

“It’s you!” She sets her basket down in the middle of the road and raises her arms to heaven as if in thanks. I shake her hand and smile back into her eyes.

Before I can say anything, she says, “Chile, Ah bin wonderin’ where you was. Sunday Ah prayed that you come an’ learn me how to write.”

I explain I have been busy trying to get other folks to register.

“When Ah gots up this mornin’ Ah was feeling something extra good was gon’ happen today. Ah clean my house real good. Ah felt so gran’ I come on down the road. Ah saw you an’ Ah knew what that good was. Look what Ah can do.”

She bends down and picks up a stick. With a steady head she writes Rebecca slowly and deliberately in the sand.

Note: I remembered this story “purely.” I’d written it down in my journal in shorthand, but I’d never forgotten Mrs. Crawford. (I actually wrote to her until she died and I still write to her daughter.) This was the first story I published. It was the lead story in Chicken Soup for the African American Woman’s Soul and it is part of You Came Here to Die, Didn’t You.

Q: Were there any surprise rewards that came to you from penning your experiences for publication?

A: There were delightful rewards. The first came before the book was even written. I was at the release weekend for Chicken Soup for the African American Woman’s Soul. There were three days of book events. We read our stories at dinner one night. After I read mine, a black lady came up to me with tears running down her face. She took both of my hands and said, “You were talking about my mother and grandmother, my aunts and all of my relatives. You made me see them in a way I never have before and I am so proud.” It doesn’t get any better than that.

I wanted to see if other folks remembered each event as I did. So, I interviewed everyone I could find who had been involved that summer. What a marvelous experience that was. I did the interviews in person and my husband videotaped each one. Why marvelous? I hadn’t seen most of them in over forty years. We’d been “in the trenches” together and seeing them was a powerful experience.

People come to my book-signings and tell me their stories about how they dealt with discrimination in the 60s. There was much more going on than we thought.

Q: Some voter rights volunteers served, went home, and lost touch with the communities in which they had worked. Fifty years later, what is your relationship with people in Pineville, South Carolina?

A: I have mentioned Sarah Butler’s family before. I met her canvassing. She was already a voter, but she wanted me to talk to her husband. She was in her sixties and she was so sweet to me. She was the place I would go when I was just a scared kid. I desegregated a black college in Columbia, SC. At Thanksgiving and Christmas my dorm closed and I had nowhere to go. So, I went to Sarah’s. We wrote and talked on the phone until she died. On her deathbed she told her daughter Lottie that I was a good one, meaning white. She said that Lottie should keep me, that we were sisters. And, Lottie and I have acted on that request. Lottie turns 93 in September and I will be at her birthday party as I try to be each year. I am Aunt Sherie to two generations of Butler descendents. I have other relationships in the community as well. I have been blessed!

Q: What were some of the difficulties you encountered in getting the book “out there?”

A: I had just begun the book when a book agent told me that the Civil Rights Movement was over and that no one would care about what I had to say. I couldn’t get an agent. I couldn’t get a publisher, so I published myself. I am not a marketer, but I am doing the best that I can. As my southern sister Lottie would say, I’m waiting on the Lord to show me the way while I plug along.

Q: What would you say is the book’s strongest takeaway message for readers?

A: VOTE! Get involved. There are problems that need to be solved. We can’t trust that someone else will solve them for us.

Q: What’s next on your plate?

A: I’m writing about my family. I come from a bunch of characters and they all told stories.

You Came Here to Die, Didn’t You is not a finished project. Making it a household word – or at least a schoolhouse word – is an enormous endeavor.

Q: Where can readers learn more about you?

A: I have a webpage at sherielabedis.com. On the webpage you can find information about the book, about me, teaching resources, discussion questions for book clubs and my blog.